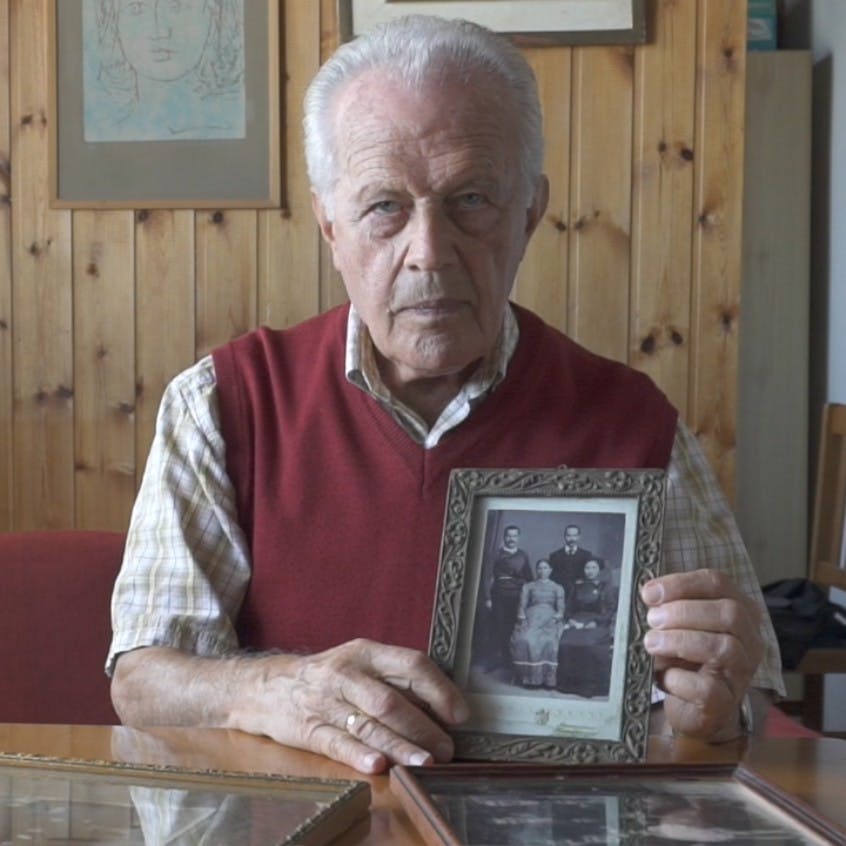

I was born in Thessaloniki, on the 14th of December 1924. With my father and mother we came south, to Athens. In 1935 the government changed, and my father wanted to go to Palestine then. It was everyone’s dream to go to Athens and go there, to Palestine. When we got there, my father, I remember, had reserved a room in Tel Aviv.

They told us that in Germany the persecution of Jews was underway. And that the various people who were there, people who were professors in the universities of Berlin and who had been driven out by the Nazis, they had only let them take their cars with them when they left. So in Tel Aviv there were these Rolls-Royces, huge cars, nice ones.

My father had reserved a place in the school, and for a while I stayed at this school, where I learned Hebrew, I learned the way they live in Palestine, and it was the start with the Arabs then. And I remember I had been very impressed that an Arab had tried to kill someone at the corner by the school. We stayed for a year, he organized the office in Haifa, and after that we returned to Greece. In 1937 I was in boarding school at Athens College. I stayed in the College until 1940, when the war broke out, when it finally came to Greece.

In 1940, when the war broke out in Greece, I felt that things would not be very pleasant. We owe a lot to one specific person. Apart from the friends who helped us, the Efraimoglou family. It was the police director general, who supplied us with fake IDs. My name was no longer Gormezano. My name was Dimitris Avralis. We knew what had happened in Thessaloniki and we expected the same thing to happen in Athens.

My father slowly managed to find a way for us to leave. And go where? To Tsesme. There were several of us-- army officers, some police officers and two or three other Jews, along with my father, my mother and myself. Nearly all the seats in the boat were full, we got in and went towards Evia. At that moment they caught us.

We were held in a house in Rafina for three days. They let the women go. At some point, the door opened, and a German officer came in, his face looked as if he had once been stabbed in it. Shouting at as, he took us outside. There were thirty of us, and he lined us all up against the wall.

And he started with the names – asking people their names. One person was shaking, forgot his name. After that, he started firing down the line of people with a machine gun. And he stopped the machine gun, he stopped the machine gun two people before reaching me and my father.

Those of us that remained, we lined up for the German to examine us. And I was telling my father: “Dad, let me go!” “Don’t move! I will save you”.

“Avralis!” My father went in, the German was sitting at a desk, two Germans with bayonets beside him. When he was almost finished talking with the German, my father said a word to him in German. This beast says: “Do you speak German?”

“Yes”.

“Why are you here then?”

He answers: “I don't know why I am here, but I am here because we were trying to go to Evia to get olive oil”.

He says: “Where did you learn German?”

My father replies: “In Hamburg”.

“In Hamburg? You’ve gone to Hamburg?” he says.

“Yes”.

“I’m from Hamburg too”.

He gave him the identity card, he tells him: “Take the ID, please listen to the German government now and nobody else”.

My father says: “You also have my son”.

“Is your son here?”

“Yes”.

“OK, call him. You can go”.

I didn’t know any German, but I knew some words. At some point the interpreter asked me:“Your name?”

“Dimitris Avralis”.

The German says, he heard it: “Tell him that his father said that you are Jews, to admit it”.

I got all upset and I said: “I am as Jewish as the Lieutenant is!” And a soldier came and jabbed his gun here against my leg. I went crazy with pain. He threw the identity card to me and says: “Go”.

The next day, my leg was bandaged with a handkerchief, it didn't hurt. This will to live! To live, I wanted to live, I didn’t even feel the pain. And when my mother heard that we were alive, that we living, we met and took the road home, to go to Agia Paraskevi. The roads weren’t paved then, they were dirt, and we walked, and we walked, I limped, we walked, and at some point, we saw two bodies hanging from a tree, they had killed them.

We had nothing, nothing. We went to this coffee shop; they had heard about us. My father says: “Can I make a phone call?” A phone call from Agia Paraskevi to Athens was a big deal back then. He called Efraimoglou. And Efraimoglou said:

“My god!” It’s you, are you truly alive?”

“Yes”, he says.

“Nothing, do nothing, you will go to this address, you will knock on the door three times and they will open, and from then on leave it to me”.

We went to this house, someone came out who was a doctor, who was with the resistance. He took us in, looked at my leg, bandaged it, and at five in the morning he told me: “Quickly, get up and leave!”

“To go where?” I say.

“Go, because the Germans are putting up a roadblock!”

We left and we went to Agia Paraskevi, we walked and went to the College, behind the college, where Mr Fylaktopoulos lived, the general director of the boarding school then, because I was in the school. We knocked on the door, the door opened, Mr. Fylaktopoulos came out and saw my dad. My dad didn't say a word. He went to Fylaktopoulos, embraced him and broke out crying. I saw my father crying and I thought: “This man who is crying, this is my father?”