Aristotelis Zervoudis, professional diver. I was born in 1964. I’ve always liked the water. I started diving as a hobby, and then it turned into something—let’s say—more serious than tourist dives and diving for pleasure. I became a diving instructor and began to work professionally as a diver. I became especially interested in the Second World War period and the wrecks of ships and planes of that time. As I studied, I became interested in finding things that had been at the bottom of the sea from then, like time had stopped, if I could say it that way.

At the end of the 90s, we were told by the fishermen in Anavyssos that, behind the island, their nets would bring up metal items—mess tins—and they even called the location ‘the mess tin wreck’. So, with my diving partner, Antonis Grafas, we decided to have a look.

Eventually, after many dives and going there often, we found some wreckage and some—what I would call metal boxes, which we brought to the surface to look at. We cleaned them up, and some engraved letters appeared, which were in Italian. That was when we started to believe we had found an Italian wreck. It took us—well, me, basically—two years, from 1999 to 2001, of going through archives—German archives—until I found what ship it was.

The Oria was a Norwegian steamship requisitioned by the Germans. At some time, it came to Greece, and, after the events of September 1943, when Italy capitulated and most of the Italian garrisons in Greece surrendered, it was charged with transporting the garrisons in Leros and Rhodes to Piraeus, from where they would be taken to POW camps. Basically, they overloaded the ship, putting people in the hold, together with the cargo.

Leaving from Rhodes on the evening of the 11th February 1944, it was heading to Piraeus during a storm, one of the worst the locals had seen; we’re talking 11 Beaufort blowing south west, storms, hail, fog...The captain miscalculated, got confused about where he was going, and the wind blew him to the right, despite the fact that he had been warned by flares from the escorts—because it was escorted by three German ships—it was thrown against the rocks. Its right side hit the south-east coast of Patroklos, and in one and a half to two hours, it broke in two and sank.

Many of those on board tried to jump onto the rocks of the island, which were right next to them, but, due to the rough sea, they were basically crushed by the ship, because the sea slammed it against the rocks, and they were caught in the middle. Of course, some did manage to get onto the rocks, and survived. Some jumped into the water, grabbed onto various pieces of wood, and were blown by the south wind to Charakas beach, where they were washed ashore.

About fifteen Italians survived, ten to fifteen Germans, and the Greek engineer together with the Norwegian captain. These survived. Some of the prisoners had been on the deck, and it was only these few who made it, finally; the rest of them, in the hold, had no chance of getting out. You can understand, everything was flooded, and this is where they stayed. At the beginning of the 50s, when a diving crew appeared here to cut up the metal—you see, there was great hunger in the country and they wanted the iron to sell it to ‘make cooking pots’, as they used to say—they cut into the cargo bays and they were all still in there.

According to what we could find, the wreck is the fourth largest in the world and, of course, the biggest in the Mediterranean. About 4100 Italians were lost. The crew was twenty to twenty-five, Germans and Greeks. And there were around sixty Germans. Bodies kept washing up for the next few months, all over the place; here, as far as Lagonisi, behind Legrena, beyond Charakas. They were collected and put in a mass grave, a little further up from the beach.

In the mid-50s, some people came from the Italian government, they dug up most of them and collected the bones, which, from what we have learned, they took to the graveyard in Bari, where they are the Unknown Soldiers of WWII. The locals knew, it’s just that after the war, from the time it was cut up, it disappeared: no more crews were turning up, they took everything, and it was forgotten. No one was interested in the history, and it was simply forgotten.

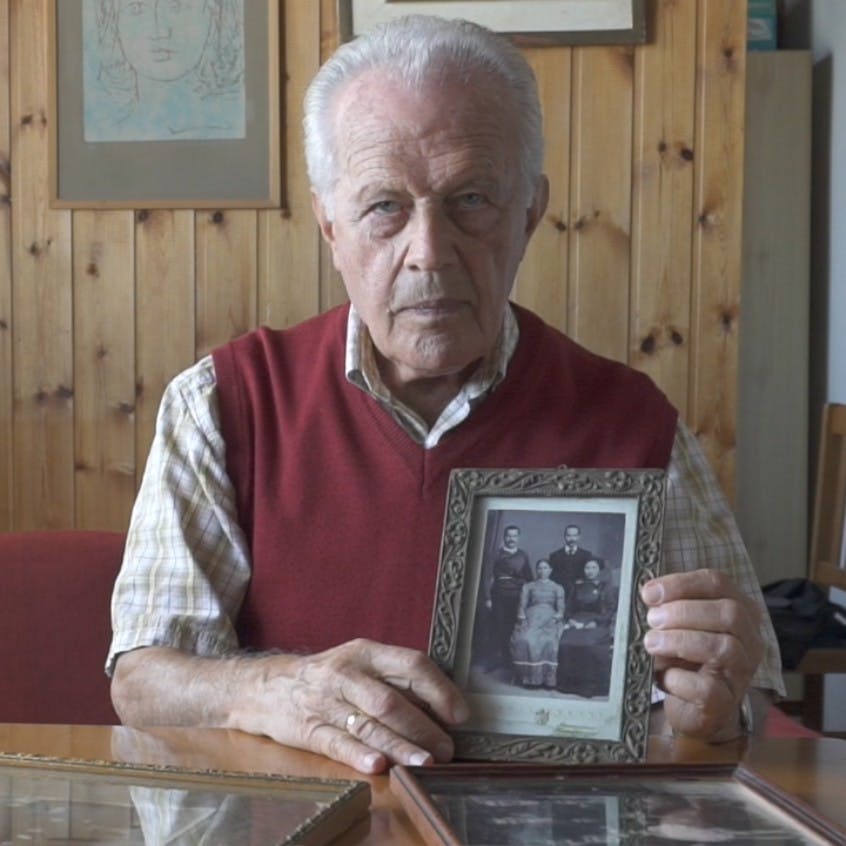

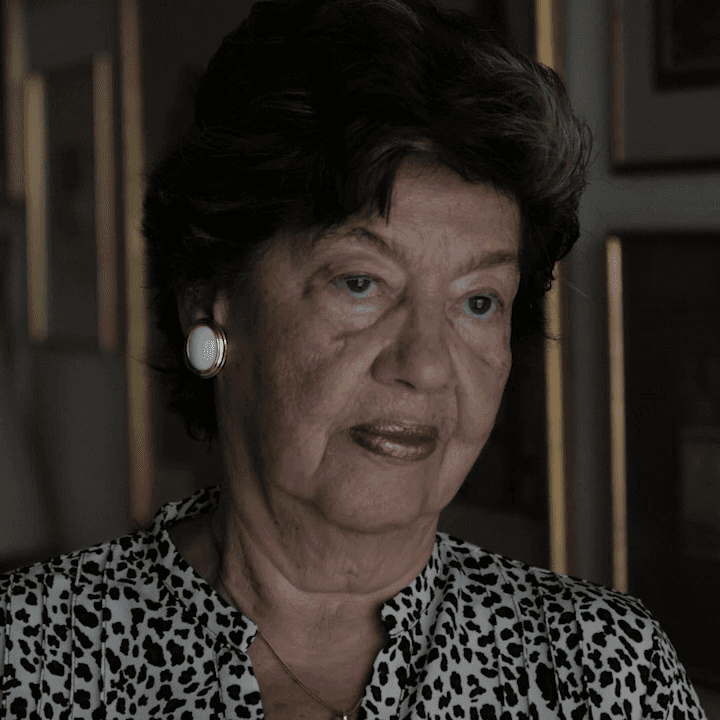

So, in 2002, I published the first paper in the world on the wreck. Nothing happened for a decade. I had approached the Italian ambassador at the time, I also gave them a video, the then ambassador and the military attaché showed no interest. Then, ten years later, I got my first communication from an Italian man and another girl, who had relatives who were on the Oria, and they asked me some things. They had been declared missing; all the families received a paper after the war saying that their relatives had gone missing somewhere in the Aegean or the Mediterranean.

After some research, the passenger manifest was found with the Red Cross. The Germans had recorded everything. And suddenly, we found who the people on board were. This is where a network began to be created in Italy between the families of those lost on the Oria. As of today, 350 families have been found. Out of 4100, just imagine...

I have managed to salvage ten of the mess tins belonging to people from these 350 families. We have had some really moving moments handing over the personal effects of these people: because a mess tin is not just a tin, it has personal items inside. You open it and it could have his glass, his fork, even his toothpaste. In one case, there was written in Italian: ‘Mum, I love you and I will come home’. Most of the Italians had written messages to their mothers on their mess tins; all of them had a message on them that ‘we want to come home’.

We delivered the mess tins there. The relatives came and, OK, that made us really happy. And when you get there, I mean, if I deliver it—the item—I’m telling you, I have been in some very strange situations. There was one time, when the sister of the man who had been lost—I had gone to Italy to deliver it—came to collect me at midnight from where we were eating and asked me to follow them. They took me to an out-of-the-way place near a river, on a bridge, over the river, and said, ‘We want you to give it to us here’, they said, ‘to be near the water’.

Over the last few years especially, now that all of these people have come here, and I have been there so many times, it’s like I have a second family. You feel a little strange there [the wreck], especially when you see things down there, you see? And in the past, there were bones, so it wasn’t just the objects, there were human remains. I had come across a skull and, while I was trying to get the sand off with my hand—so that we could take some photographs, because there were bones all around—it was picked up by the current; it rose up and drifted in front of me, there, where I was. It was a really strange feeling. I think it scared me a little.

We placed a plaque dedicated to the shipwreck victims who were—let’s say—surrounding the wreckage. I was awarded a title and a medal by the Italian State. OK, it’s some moral satisfaction. I don’t think that the Greek State has realised the importance of the history or, at least, the emotional impact of this shipwreck. When you realise the size of the losses—I mean, it’s like a whole city—you can understand the horror of war. You see that peace is the most valuable thing there is.

We are not finished with the Oria. Because this is how the families want it. We all want to find something of theirs that they can have. We constantly get messages: ‘Did you find something belonging to so-and-so?’; ‘Have you found something?’; ‘Have you found this name?’; and, OK, we try to help them. Because my father fought in ‘42. He went as a volunteer. So, if something like this had happened to him, I would want to know, to find out where my father was lost or where he was.