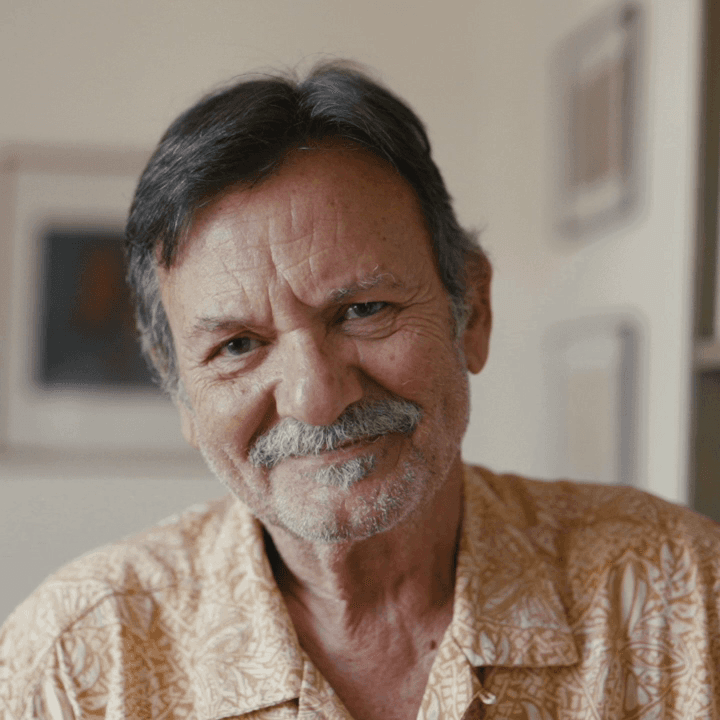

Not just anyone can work on the Acropolis. From the moment you climb the Acropolis for work every morning, you say, ‘I am special’.

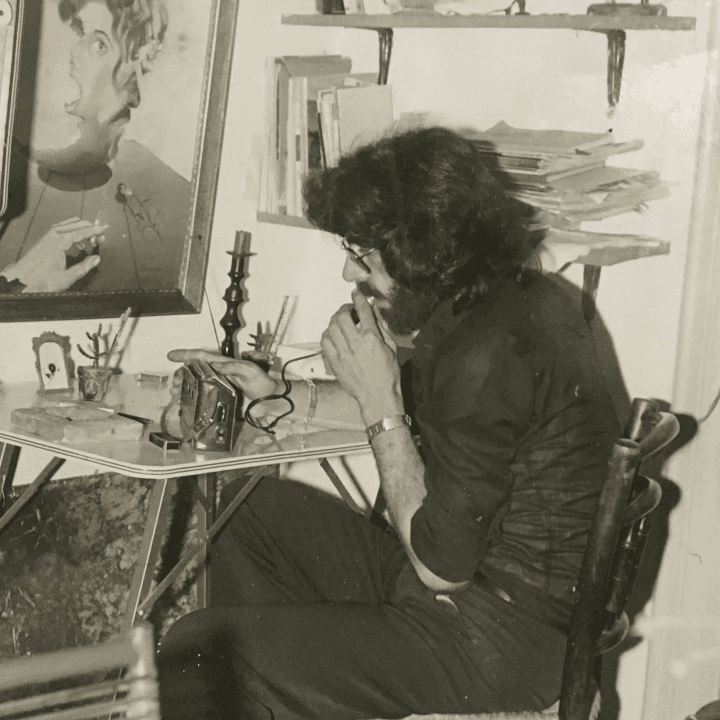

I was the longest-serving worker on the Acropolis. The first photograph that I have in my career, when I came here to Athens, as a young boy, was one that the wife of my boss sent me to take on the Acropolis. And, in fact, I am wearing... I was fifteen, and I was wearing a jacket and tie! I mean, how do you dress for the Acropolis?

I was born in a village in Epirus called Voulista-Panagia, it’s mixed, it’s a double name, Voulista-Panagia. When I had finished the first two years of high school, I went to Ioannina for work. I got there when I was about fifteen and decided to come to Athens. One fine day, I left, got on a bus, nobody knew – there was no one to tell, as both my parents were in Germany with my two siblings [they had gone as migrants]– and so, one fine evening in August ‘68, I found myself in Omonia, at the age of fifteen. It goes without saying that I had nowhere to go, I spent my night there, and from then on, I started to build my career, to work on my own, because that was my aim, as a free man.

We had nothing. As I said, we came from the village with a pair of plastic flipflops and a t-shirt, for summer, but nothing else. Nothing else. We went to bed hungry. I had a pillow. I held it to my stomach to put pressure on it so that I wouldn’t feel the hunger. We had to fight. In life, we start from zero, you have to fight, you have to kill the beast.

The years passed, and I met a friend, Monokrousos, the engineer, and he told me, ‘I’m putting together a crew to stabilise the rock of the Acropolis’. And we started working on the rocks of the Acropolis. At that time, I worked as a borer. I would bore into the rocks, the rocks that were ready to fall, and, when we found something stable behind that rock, we would secure it with an anchor, a special rock anchor, to stabilise it.

This work went on for ten years. There were many of us on the rocks. There was the first team, which cleared the rocks of the vegetation that had grown there, prickly pear trees, etc. They went ahead and we followed, we were the team that stabilised, and a third crew sealed them, so that no plants would grow there again. That’s why the rocks of the Acropolis seen from Koukaki or Plaka, don’t have any vegetation.

A lot happens on the Acropolis. In our time, then, it was less crowded; you had human contact. On the road, would say a ‘good morning’ to a foreigner. Now, from what I know, thousands come every day.

One fine day, someone asked me if I would let him propose to his girlfriend in ‘the greatest temple in the world’, because we believe that the greatest temple is the Parthenon. And I said to him, ‘OK, let’s go in and get you engaged’. So, we took him inside. The girl didn’t know what we were talking about, and he gave her a note and the ring. The girl went crazy, completely crazy! She was crying, and she even kissed me first and then her young man!

Someone brought their mother’s ashes from England, and he wanted to scatter them around what we call Athena’s Olive, the one behind the Caryatids. His mum had wanted her ashes to be scattered on the Acropolis, because she visited every year and loved the monument, and this was her wish. He wasn’t allowed to do it. He said that he had asked some people who told him, ‘We can’t do that’. And so, he came to me. And I say, ‘OK, let’s do it’. And we did it in secret. We lifted up the wire rope, got in around the olive tree, and scattered his mother’s ashes. We were all very moved. He sent us photographs and a box of chocolates. We did those kinds of things. A friend might come, or one of my siblings, and I would show them around. Now, things are stricter, you can’t go inside.

I remember one time, there was a girl – she would have been thirteen, fourteen years old – and they brought her over from America because she was very ill. They had promised that when she got better, ‘We will take you on a trip to Greece’. And, as they were climbing up the propylaea, someone who was accompanying them who spoke Greek saw me in my work clothes, and said, ‘Do you work here?’ I said, ‘Yes’. And he says, ‘We told her we would take her to the Parthenon. She thought we would take her inside the Parthenon. And now we find out that can’t happen’. I said: ‘It can happen on one condition: that no one else comes with you’. I took the girl and took her inside. And the girl, of course, went mad with joy. I have no idea what happened to her later, but when we left, she was so happy. It’s worth it to do these things. ‘The girl’, he told me, ‘was at death’s door’.

Once we had finished the stabilising work on the rock, I stayed on it for another fifteen years. We were a crew of four and we were responsible for the lighting of the Acropolis and all the machinery. In other words: cranes, lights, offices, air-conditioning, anything that was up there, we were responsible for.

Conditions were difficult. The heat was intense... On the Acropolis... When we say ‘it’s hot in Athens’, let’s say 40 degrees, on the Acropolis it’s 45 plus, because the rock reflects heat, it’s very hot. Many times, those when we were at the top of the cranes which you climb up on the webbing, it was very dangerous, at noon, I don’t know, in the summer, with a wet handkerchief tied around our heads, soaking, so we wouldn’t be burned alive. That was barbaric. Or when, let’s say, we cut the boom of the crane, three or four metres that were two and a half tons, and we cut it in the air.

When the power went down and there were storms, we had to go out in the storm to repair it. And the others were sitting inside, and even shouting, ‘Come on guys, what’s taking so long?’ And you could see that it was dangerous. In front of the old museum, there was an old breaker panel, huge, made in the 50’s-60’s, I don’t remember when, and it was outside, exposed. And the power on the Acropolis went down. The general breaker switches on that panel... Don’t imagine they were like the breakers in your house... They were huge things, OK? And we went out in the storm to turn them back on, to fix it. Flames started to burst out and I saw what was happening, and I said, ‘Nikos, are you OK? What are we doing here? Do you want us to get killed?’ Because that thing was a wreck. Of course, it was replaced later, when the museum was renovated in 2004. Because you didn’t know where the power was leaking from. And we’re not just talking normal electricity... It would fry you, OK? Not even your bones would survive. There, I really felt that I was in danger. But as long as we were on the Acropolis, no other crew came in. We were responsible, we accepted our responsibilities and everything, and we fixed it.

What’s really upsetting is everything that went on the Acropolis with suicides. During my career there were sixteen. Two happened almost in front of me. One was right in front of me. I was down in the rocks, and they fell right in front of us. Another threw himself off in protest, as he had caught his wife with another man. I helped the fire fighters get him down from the rocks, because where he fell was a blind spot. When I got back up, the group hadn’t gone because they were going crazy, they’d all gone crazy with grief. I said, ‘What happened, guys?’ And the translator, the guide with the group, told me that, ‘Everything happened last night at the hotel, and he told her that “We’ll deal with this tomorrow”. And this is what he meant’.

I’ve seen all the secrets of the Acropolis. There’s nothing like the strange things we kept finding. We lifted up a cover, let’s say, and we had no idea what we would find. Where the flag is, for example, it’s a platform all the way down, with a metal staircase in the wall, like those on a ship. In the Propylaea, to the left as you go up, there is cover that had a water tank underneath, which was famous for secretly supplying those who were trapped on the Acropolis then, with Androutsos and the rest [during the siege of the Acropolis by the Ottomans during the Greek War of Independence], and the Turks didn’t know how the hell they found water to survive up there. We discovered things that had been forgotten.

Night up there on the Acropolis is magical. Those of us who went up at night... At night you really feel like you are close to God. We had lightning rods and all that, and we went up to do maintenance, and that meant going to the top, the very top of the top, OK? On the Parthenon. You feel like it’s just you and the monument. There is no noise, nothing like that. You can’t go any higher. And there, you really get a feeling of awe.

Of course, at night in the past, there were giant tortoises up there. We had a little fox that came out at night. They all lived there. We lost them after we cleaned the rocks; they disappeared. We had blackbirds who spent the winter there. The blackbirds were permanent, they didn’t leave to migrate north. We had lots of cats on the Acropolis, and these cats were famous. There were no more photographed cats in Greece.

On Sundays, holidays, or other feast days, the evzones of the Presidential Guard would come up. Of course, they came up in the traditional evzone uniform, with their hobnail clogs. And they came up all in step together, ‘crunch, crunch’. It was a little difficult for them to climb up the Propylaea, because the Propylaea is made of marble and people slip, but anyway, they had been trained. One time, I saw one of the officers of the Presidential Guard giving an order in front of the Caryatids, and they all stopped, and the soldiers – the evzones – turned and shouted, ‘Good evening, girls!’ to the Caryatids. I hatched a plan with a colleague and said to him, ‘We’ve got to mess with them. No way we’re not!’ So, I went inside the monument, hid behind a Caryatid, and the moment they said, ‘Good evening, girls!’ I came out to the edge and said, ‘Good evening, boys!’

I had no boundaries. I didn’t care if it was the president of the republic, or if they were famous actors and the rest of it, I spoke to everyone as if they were my friend, as if they were my father, like they were my sister, I didn’t really care. Like I spoke to Papoulias [the president] quietly in his ear, oh I don’t know, ‘Mr President, I have good tsipouro from Ioannina!’ And he replied, ‘I can’t now, I’m the president!’. OK, yes. But the next day, he sent us a bottle of tsipouro as a present; he bought us a drink. He was a good man.

Agios Charalambos is the patron saint of marble and stone workers. He is the craftsman, let’s say, Saint Craftsman. So, on his feast day, there is an event organised by the crew on the Acropolis. In one of the workshops where the marble workers were based, they left the benches where they carved marble all day and held a dance, each of them bringing his wife, and all the rest of it, some meze, a little wine... This started around 10-11 and could go on until 5 in the afternoon. The Acropolis closed, and they, I mean we, carried on. Of course, when I retired, I was still there for the party every year. I didn’t want to – and I haven’t – lost contact with my colleagues.

The whole crew was very low key. However, we were in charge, in the sense that, if there was any damage, we took the lead. We ran around, and everyone knew us and loved us. We never refused to do a favour. We never said, ‘I’m not doing it’, or, ‘Leave me alone’, etc. There wasn’t any of that in our crew. They loved us in the crew, and whenever I go now, everyone loves me. I know it. I see it. There is no one there who doesn’t love me. You go to see them for half an hour, and you end up staying until the afternoon. I was like a boss. Wherever I went, they greeted me. I couldn’t have been more of a boss.