At some point, the decision arrived: all the young detainees would be released by the Regime of the Colonels. It was the best day ever. We got our things together, went across to Lakki, we found somewhere to leave our stuff, rented bikes – about 30 of us – and went for a ride around Leros. We sent telegrams to our families. I sent one to my family in Rizo in Skyrda, a telegram of just three words, ‘I’m free!’

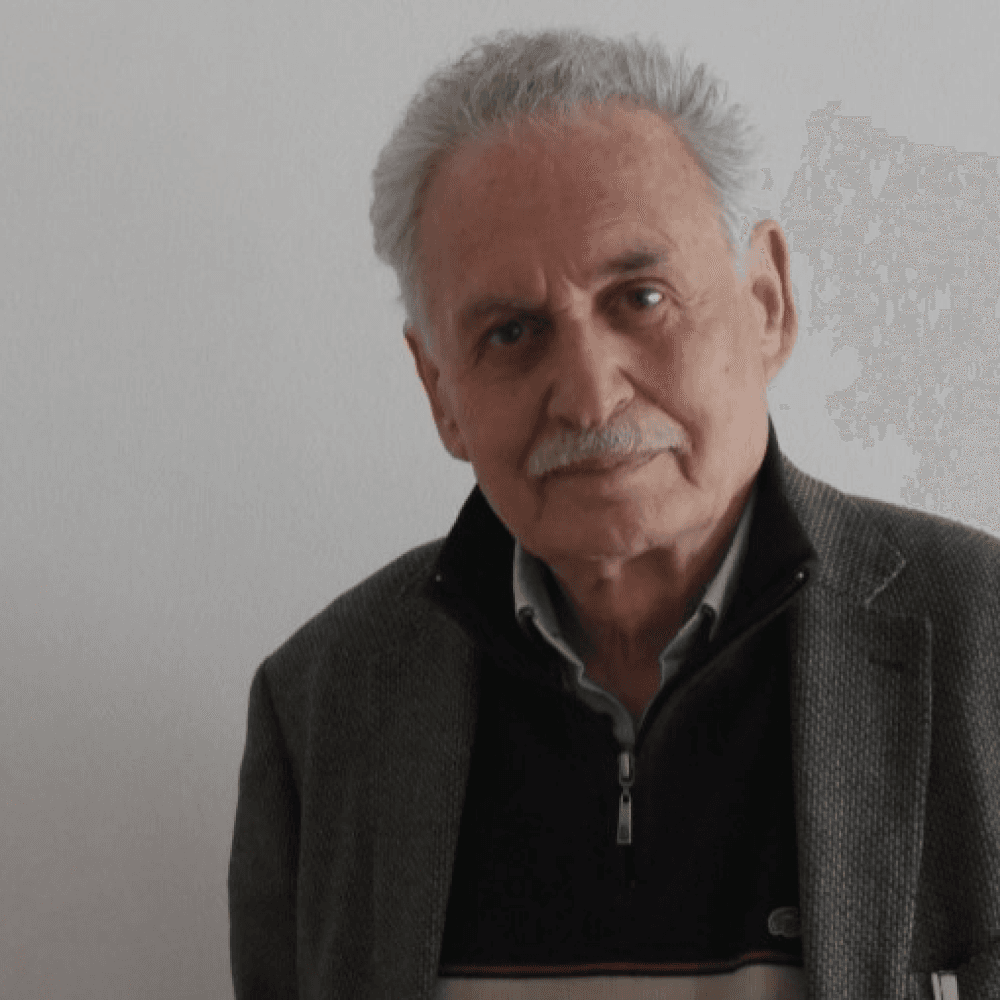

I was born in Thessaloniki in 1947, but most of the time after that – my childhood – I spent in Skyrda. From the age of around eight or ten, I was really quite politically aware, due to my family. In those days, there was the United Democratic Left party, the EDA. My parents were communists and were in close contact with the EDA. From a very young age, I followed the election results. I used to read the Avgi newspaper whenever my father brought it home. When I turned 18, I came to Thessaloniki and joined the Lambrakis Youth.

I joined the Lambrakis Youth in Ambelokipoi as soon as I arrived. It was a powerful youth organisation, there was Yiannis Chalkidis, who was later killed by the Junta, Yiannis Katsaros, who later became an MP of the Communist Party, and I took on the cultural part. We cleaned up some of the squares there ourselves. We would go at weekends and try to sort them out, because the state of western Thessaloniki in those days was very basic.

We were regularly persecuted by the police. Anywhere we gathered, there was always some policeman following us. There were arrests and clashes, a lot of that kind of thing, but that was just a sign of the times, and we were used to it. We had the recklessness of youth in those days, and we really didn’t care.

We had already been prepared by the Lambrakis Youth that there was talk of the impending dictatorship. On 21 April, I was working for the Express newspaper, and when I saw the tanks and army coming into the Vardariou area, Egnatia, and towards Tsimiski, I understood that from then on, I had to be careful where I went and should probably lay low for a while. We were members of Lambrakis Youth, and the police would be keeping an eye out for us. I went to the house of some relatives that were above suspicion, in the Cassandros area. I slept there for one night, but on the second day they got scared. They basically said, ‘If you can, you should leave’, in a polite way. So, on the third day, I had to leave. I’d no idea where I would sleep; if I went back to my village, I would be arrested for sure. I had no choice but to go back to my house in Ksirokrini. Within an hour of me getting there, the police arrived. They arrested me and my house mate and interrogated us.

My house mate was a right winger, and he burst into tears inside the police station. I was cooler. Comrades had warned me a long time ago that if you were arrested this and that would happen. We were more or less prepared. In the second phase, they took my house mate, who they'd put in solitary, and questioned him separately. I didn’t know. He told them some things about me, because I had a lot of books that I’d hid in some sawdust in our yard – we lived in a detached house. During the following interrogations, the police kept asking me where my books were. I didn’t know that my house mate had already been released after telling them everything; basically, he had snitched on me.

They kept about 15 or 20 of us in a small cell for a week. They were all local mayors, or councillors. I was the only young person. One particular man, a policeman, whose face I will never forget, would beat me every day for 5 to 10 minutes and then back I’d go to the holding cell. They wanted me to make a formal statement that I didn't belong to the left, that I regretted having joined the Lambrakis Youth organisation, and that I was now on the side of the ‘nation-saving revolution of 21 April’. All of this in the 9th Police Station of Thessaloniki, in Santaroza Street, opposite the railway station. They brought me in every day, took me for questioning. The same story every time, ‘Where are the books? Make a statement.’ I didn't. On the seventh or eighth day, they gave me a small paper to sign that said, ‘Yes. I’ve been arrested.’ They hadn’t given me that paper at first. I now understand that, possibly because of my youth, they wanted to let me go once I’d done what they wanted, but I never made that compromise, and I was sent with the others to Gyaros.

On the way, we stopped to pick up some comrades from the police station in Vardariou. From there, they took us to the transport unit in Filippou Street. By chance, I met someone from my village there; he was there for other reasons. I said to him, ‘Let my parents know. Tell them Theodoros is inside’. We had a lawyer with us. That poor man had been in and out of jail and in exile his whole life. When he’d got out of jail, he’d got married straight away, had a baby, a little girl, who came to say goodbye to him there. And the baby asked him, ‘What are you doing here Dad? Why didn't you come home last night? Why don’t you come...’ It still gets to me. She must have been two or three years old.

Anyway... The next day, we all left for Athens and boarded a boat. The Piraeus-Syros line. There were some tourists on the boat, and they took pictures of us all wearing our handcuffs. After two or three days on Syros, they took us to Gyaros.

I quickly understood why so many prisoners, older prisoners, talked about this dry island. They actually called it ‘kersonisi’, which means ‘dry island’. This was why it was uninhabited; they was no way you could live there. The island was also used for exile from the time of the Roman Empire. We got off onto the small jetty. There was a strong wind. A really powerful wind.

Some Macedonian friends recognised me from way off and started shouting. But I was taken together with the Athenians, including Ritsos and other leading figures of the left, to the prison building. The Macedonians were in tents on the right side of the bay, which had been made specifically for camping. When I got up to the building, it was full of prisoners, and they had me living for 10-15 days with the Peloponnesians at the back of the building, with a family from Zacharo in the Peloponnese. There was the father, the son, and some of their relatives. When Gyaros started to empty, as many prisoners signed the declaration and left, all of us lived in the prison building. Then it was the Athenians and the rest of us who’d been arrested three or four days after them.

I understood why they did it, signed the declaration, I didn’t blame them, depending on the reasons why they left. For example, at one point, they took us youngsters somewhere separately. In the same tent, there was a – how old would he have been? Fifty? Somewhere around there – who in his previous life had been in and out of jail. He was released from prison under Georgios Papandreou, married and had a ten-month-old baby, something like that, and then, bam, along comes the Junta and they arrest him. So, he signed the declaration with tears in his eyes, and told me, ‘I’m leaving. Not for me. I’m leaving for the baby.’ He had to go.

We younger ones had another kind of conversation because Aris Velouchiotis had signed and then carried on the fight once he got out. When there were three or four of us together, we’d say, ‘Maybe it's not such a bad idea to sign and get out of here to get organised and fight against the Junta. Because we’re achieving nothing where we are now.’ We had these conversations, but somehow it didn't feel right. I mean, at that moment we would be betraying the struggle. The others, who were older, seventy or eighty, had been in the old prisons. Each one of them had spent 10 to 20 years in prison. They said: ‘Do you seriously think that I'm going to sign now that I’m old?’ They never signed.

These older ones had a saying, ‘Love your cell, eat your food, and read a lot’, or something like that.

‘Love your cell’, in other words, you have to come down to earth and adapt to life in jail. There was a huge dormitory in Gyaros, for 100 to 150, I don't really remember, but about that many. There must have been around 100 of us. The mattresses were straw; we slept on the floor.

‘Eat your food’, means to look after yourself; we cleaned the toilets really well. They were comrades cooking in the canteen. In fact, one of the cooks was Spyros Chalvatzis, who went on to become an MP for the Greek Communist Party.

‘And read a lot’. Most of us read. But even those who didn’t know how to read, found someone from their area, someone from Kefalonia or from Edessa, and discussed things they were interested in. Most of the young people read. In the letters we wrote to our relatives, we always asked them to send us books. We set up our own lending library where you could go and borrow a book. Of course, left-leaning books were banned. They could see them, everything was checked, even our correspondence, and many comrades wrote their letters in a conspiratorial way, I mean by hinting at things.

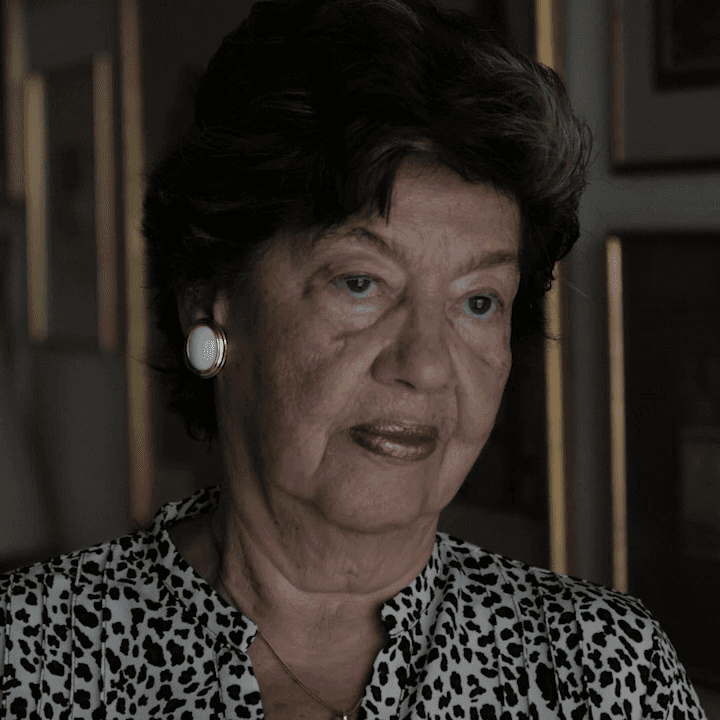

There were women in Gyaros and there was a special space for women. We had Vaso Katraki, the engraver, who even gave me a stone with a flower engraved on it. I specially remember when they brought in the wife of Fotopoulos, Mimis Fotopoulos, the actor. I didn’t know her. All at once, all the women from Athens came to hug her, and she began to tell us what Fotopoulos had said at the police station. When she asked for permission to call her husband, they let her call. He thought she had been released, and said, ‘Are you free?’ ‘No. I’m leaving for Gyaros.’ Then they brought her to us. But she was really happy to find herself in our kind of environment. She laughed easily and had a great sense of humour.

I saw famous people – people who I never thought I'd be able to meet up close – in the same space; such as Ritsos and others there, all the politicians. For me personally, they were demystified, because I’d always had a tendency to be sceptical, even though I was young. I understood that famous people are just like us, which is why we shouldn’t underestimate ourselves. We should state our own opinion on a subject and not become a mouthpiece for someone who is considered famous or superior to us.

Someone on Gyaros who really influenced me was a lawyer from Thessaloniki, a Jew, called Mosad. When someone burst into our dormitory one day, there on Gyaros, and said, ‘From now on, I will be your dormitory chief’, Antonis Mosad, the lawyer from Thessaloniki, replied, ‘When you go to the commander of the police here to represent us, you must say, “I represent everyone except Antonis Mosad”. Because I’m here due to a dictatorship because I am for democracy. We haven’t voted for you, and since we haven’t voted for you, I personally, do not recognise you.’ At that time, I didn't have that kind of culture, I wasn't that sophisticated, I thought he was wrong. But, after everything I went through, I understood how right he was, and that when you haven’t elected someone, he can't represent you.

We spent two or three months on Gyaros, and then Leros. Somewhere around 15 months. They put us all on a big ship, those of us who were left, because most had made the declaration. There had been 6 to 7 thousand prisoners. There were 2,000 of us left.

Things were slightly better on Leros compared to Gyaros, because we could see the village of Lakki opposite, and we felt that there were other people nearby. We knew that behind it there was the well-known psychiatric hospital of Leros. Conditions were still miserable; there was a barbed wire fence around the area. We were still in a dormitory for around 150 people in bunk beds.

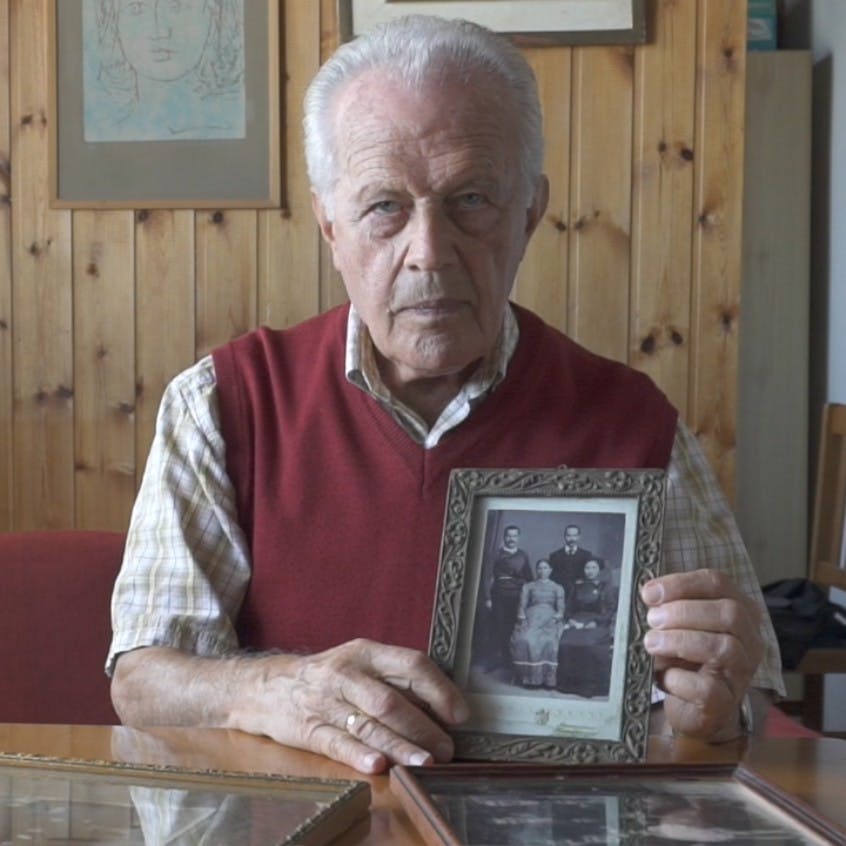

In the bunk below me, there was a civil engineer from Athens, his name was Spyros Makris. He was a friend, a close friend, of Syros Pantzas, the father of Pantzas the actor. So, because Spyros Pantzas would come to our bunk every day, I began to discuss things with him. He was a great intellectual. He wrote a lot of poetry, really good poetry, and sent them to a radio station in Moscow, and one of them won an award. He sent the poems under a pen name and got the first prize. I think the poem was called ‘The Chrysanthemums’.

He would tell me that he had two weaknesses in his life: women and the Greek Communist Party. He spent most of his life in prison, in Ai Stratis and so on. He also told me that he had fallen in love with a girl on Ai Stratis, but the Party forbade such things. He disagreed with the Party, and they threw him out for it.

Pantzas influenced me a lot ideologically, as did Makris, the old man who slept below me; both of them sceptics by nature.

Along came the 21 April 1968, and the Soviet ambassador celebrated the 21 April with Papadopoulos. The damn Soviet ambassador! This seemed like betrayal to us. The Greek Communist Party wanted to gloss over this, and the news they sent us was that the Red Cross of Azerbaijan, which was a soviet republic, had complained about our imprisonment. The anniversary of the 21 April in ‘68 fell on Easter, and they wanted to bring us goats so that we could celebrate Easter. They brought the goats and all the rest of it, and we threw them in the bin. We threw away all the food we had. We all went on hunger strike.

Thankfully, we all had a streak of resistance left in us. Despite this, there were those of us who were pressured by their families. One poor guy, from Katerini, if I remember correctly, because he'd got a letter from his family... when we were sleeping... He was in our dormitory... At 2 or 3 in the morning... Jumped out of the window and killed himself. Another, a friend of mine, a lawyer, was sent a letter by his girlfriend: ‘If you don’t sign the declaration, I’m leaving you.’ So, the poor man was forced to sign the declaration. He left in tears. Although he was a good leftist, this was a very dark point in his life.

Meanwhile, when I was on Leros, we were summoned to go to court in Thessaloniki, as defendants, because when we were in the Lambrakis Youth we had set up illegal megaphones and made speeches, which, they wrote, ‘Disturbed the peace and pleasure of the residents.’ So, we went back to Thessaloniki. I expected to be found guilty and be sent to prison in Genti Koule. However, unfortunately, I was found innocent, and was sent back to Leros.

There were some young people on the boat who had a transistor and were listening to music that I was hearing for the first time. When you’re out of society for a year or so, things happen that you are unaware of. You don't see the changes.

We also picked up some news. I later found out that someone had smuggled a radio in. He told the news to one of us, who told it to another, and he to another, and so on. And so, I eventually got some news. Usually, the news was good, and gave us courage. We didn't know that the Greek people had somewhat come to terms with the Junta, many of them.

In Gyaros, I’d met a journalist, Dimitris Palios, who wore a straw hat, on which he wrote ‘Mamma ritornerò’. ‘Mamma ritornerò’ means, ‘Mother I will come home.’ Up until then, I’d never thought of learning Italian. When we went for roll call, because they counted us every day, like we were sheep, I asked him, ‘What does that mean?’ And he said, ‘Mamma ritornerò’ means ‘Mother, I will come home.’ I liked that. ‘What language is that?’ ‘Italian.’ So, our friend Dimitris gave us Italian lessons.

I learned Italian in two and a half months. And with the Italian I learned, in the following years Italy was the first country to supply Greece with products and I worked as an interpreter, and for 30-40 years I was going to Italy as an interpreter, because of the Italian I learned in Gyaros. And, when I went to Leros, I became a teacher of Italian, me at 19 or 20, had students of 75 to 80 years old. I went on to learn French. And then German. But I didn't finish learning German.

At some point, the decision arrived: all the young detainees would be freed by the Regime of the Colonels. It was the best day ever. We got our things together, went across to Lakki, found somewhere to leave our things, rented bikes, about 30 of us, and went for a ride around Leros. We sent telegrams to our families. I sent one to my family in Rizo in Skyrda, a telegram of just three words, ‘I’m free!’

Freedom is the most precious thing we have. I was overwhelmed with joy; I missed my mother so much. I was struck by the love you feel when you miss your mother.

I arrived in Skydra by train. My grandmother was waiting for me with a young communist who had lost his mother in the civil war. They took me to the village by car. There were about 50 people, most of them women from my neighbourhood, waiting for me. And, OK, it was very emotional. But the most emotional thing of all was our dog, who I hadn't seen for two years, and you can't imagine how mad he went. That reception was unforgettable.