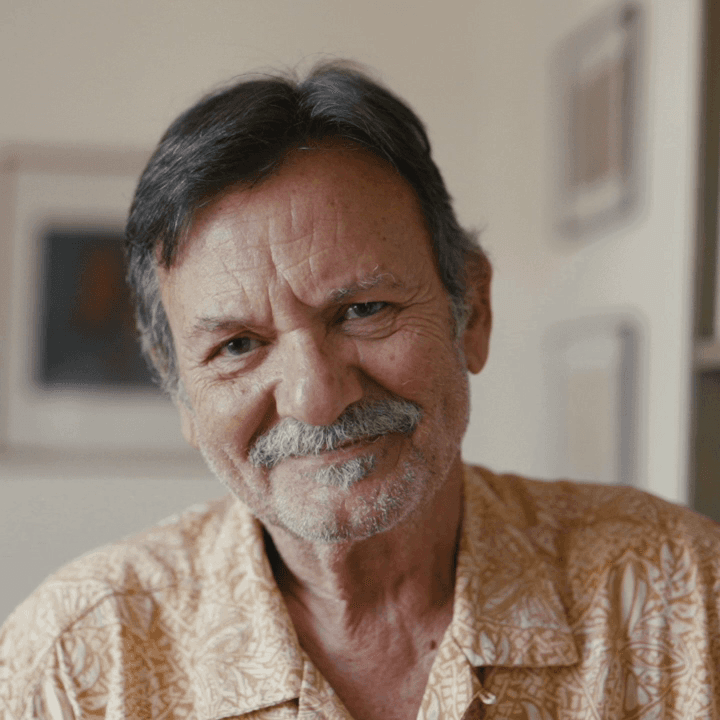

My name is Kritonas Anastasopoulos. I grew up in a large family. I was the first of five children. We were five children.

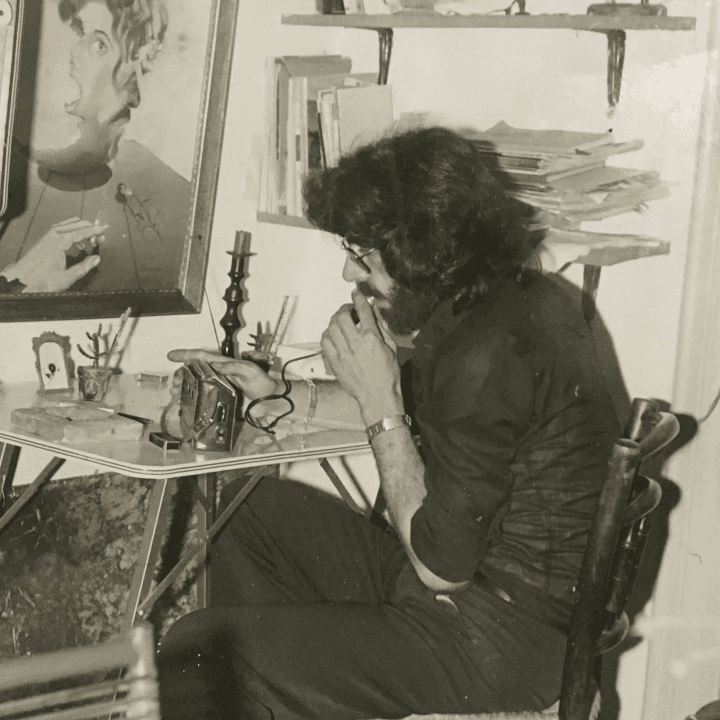

This is how, at a young age, my father chose to rebel. When he was around twenty, while he was studying political science, and, at some point, he decided to leave with my mother and go to Germany and take up puppet theatre. And around that time, I was born. I then came to Patras. And from a very young age, I also trod the boards.

Characteristically, I remember the smell of cooking meat on the feast days. We made our way through all the villages of the Acahaia Prefecture, Elis, the wine festivals, for example, the watermelon festivals down in Filiatra... We would load the... with the scenery, the puppets, the magic tricks and that’s how we went from village to village. We set up, and then all that waiting, the commotion, until we started the show. The show starts, and you have to hold them, hold on to the audience, keep their attention. You’re not in a theatre, it’s an open space outside: there’s a big difference. I remember proudly sitting backstage and holding up the backdrops. And it was often windy in some places. And that wind was my father’s worst fear. He made people laugh. And people needed to laugh.

One summer, while we were putting on a show, someone came and brought us two video cassettes, some ‘Circus of the Sun’, ‘Le Cirque de Soleil’, in Canada, which had started at the beginning of... the 80s. I put it in. There was a big number with Russian acrobats, there must have been around fifteen of them, beautifully choreographed. It was a jewel, anyway. I identified with it 100%, I was moved. And I said, ‘That’s what I want to do! That’s what I want to become!’

And I began to do acrobatics. I had to start training somehow, at the age of fifteen. At that time the hormones of adolescence were boiling! I broke hands, I broke feet... And despite this, my father – because he could see that I was working, that I liked it and it could become something serious – so that I could get better at it, we left in the summer of 2005 for me to go to my first summer camp. It was a National Circus School in Budapest, in Hungary.

The trapeze, the traditional Russian trapeze, is the one where you have the net below. You climb up on rope ladders and when you get up to about eight metres there is a platform, at nine metres. And at nine metres, you grab the trapeze. There is the guy opposite whose is the one who holds you, and you start, you jump off, and he catches you. I did that twice, I mean at a height, a height of seven metres, and then I said, ‘Guys, I’m not going any further! I’m not!’ I had acrophobia. I was scared of heights. I remember now, up in Sychaina, climbing a mulberry tree with my sister, who was younger than me, and I couldn’t climb up...

I went back to Patras. Together with my parents, I decided to start a gymnastic high school, so that I could train in the mornings. I started to train on the trampoline with a top trainer, Dimitris Stefanopoulos. He was my trainer for the trampoline. I sweated buckets there. I put my heart into it and didn’t... My adolescence was very disciplined. And lonely. I gave myself a goal and set my sights on it. I was young, and I was only thinking about ‘Ithaka’ [the destination]. I didn’t notice the journey.

It was the summer of ‘07, and auditions would be held in June. École Supérieure des Arts du Cirque, in Brussels. My parents gave me their full support: we rented a multivan, piled in, and off we went. Belgium here we come! And I went to audition. Eighteen years old, a nervous kid, but full of energy.

In the first stage you did general floor acrobatics, for flexibility and strength. If you passed that stage, you did the trampoline. If you passed that stage, you presented a piece that you had prepared, everyone had their own solo. I was one of the best on the trampoline. The school there noticed that, and they said, ‘He could do the see-saw’. They introduced me to two companions, Antonio and Raphael, and they said to us, ‘You three are going to start to specialise in what is called Korean see-saw’.

I had never bounced before. I had never done jumps from a see-saw. At first, it takes you... about two months? When you are a beginner with a beginner, you don’t learn, the jump is not easy to learn. You mess up your knees, your back, you fall again and again... I was full of shin splints... We had Yuri, a Russian trainer, a tough nut. Very good, famous, but OK, a classic macho Russian trainer. A very temperamental man. I learned a lot of things there. I learned French; I picked up French as I went along. I was thrown in the deep end. For six months, I had a constant headache trying to understand the conversations, to become a part.

Everything went well with the other two boys. We learned together, grew up together, and we became a ‘collective’, a team. Our team, the one we had formed, was called Acrobarouf. In French, barouf is a noise, the sound you get in a closed space, when you’re in a bar, when a lot of people are talking very loudly. This noise: Acrobarouf. And for nine years, off we went, doing the festival route in Europe, to many places; we did cabaret in Germany...

The circus is something different. There isn’t as much individualism as there is in dance. In the circus, there is that wonderful thing nomads have, which is like a big family, whether you are in caravans with your own circus tent, or performing on national stages, there is always that idea of family, the collective. You have a different psychology. You are not floating in an ocean, where you are on your own and must do things. The idea of freedom has become so embedded, the concept of the free market, competition. In the circus, if you are good, you can make a living from that, outside.

The basic thing to be careful of is injury; one knock can keep you out for a long time. We had a chant before we began a performance of Acrobarouf. We would shout, ‘Ouf! Ouf! Ouf! Acrobarouf! One important thing: No injuries until the end!’ There could be two thousand people out there, lots of chatter, and we had to get into a warrior’s state of mind... And we always said, every time we began, ‘The most important thing is to enjoy this performance; we do this because we love it. We must stay in one piece and free of injury to the end of the show’.

I was twenty-one – twenty-two when the Cirque du Soleil got in touch with us regarding a new production. We were in a privileged position, for Cirque to contact us. And we decided to sign a contract and leave Europe, to go with them for two or three years.

We didn’t really grasp the magnitude of that decision at first. Two and a half thousand people worked in the premises in Montreal at that time. It was a massive circus factory. We got there, and it took us about a week to orientate ourselves inside that labyrinth. I’m telling you; it was huge. Huge!

The production we were in, in the Cirque du Soleil, was Amaluna. We did around three hundred and sixty performances a year. We did double and single performances, around eight to ten performances a week when there was great demand.

The chapiteau, the tent, the tent of Cirque du Soleil is very beautiful. We’re talking about a circus tent for two and a half thousand people! It’s fifteen metres, twenty metres high... We began to realise the magnitude of the thing, of the titan that they had created there. It’s... You go up on stage and something is created... Like time stands still. An amazing experience.

We stayed nearly eight-nine months. At some point, we decided to finish up and come to Europe, and work at our own pace, to design a touring show. And, I can say, it went really well.

Later, I met Maya, my wife, who is from Switzerland, and we started our life together. We had two children, which is the greatest gift. We did some productions together, which were really marvellous. They are like children; they grow as we grow, seeing how the body matures, how it ages and how that can also be communicated, in a different way.

We have played some unbelievable places. In so many places, I’ve felt complete. When someone comes up to you and shakes your hand, and either wants to take a picture or tell you, ‘Guys, what you do is an art. It touched me, it... it...’, you feel… You feel complete. There are times you’ve performed for fifteen people and two puppies. And you say to yourself, dude, after the conditions on the journey, the carrying, the setting up, the striking the set, having to leave the same day for Paris... Despite all that, you do it, and even then, you say – as soon as you finish the performance, which might have gone badly – you say, ‘Even that was worth it! We know why we do it’.

This life as an artist is a declaration, it’s a statement that, ‘We can live like this. We want to live like this’. It’s possible that the artist has no choice. They can’t live without it.