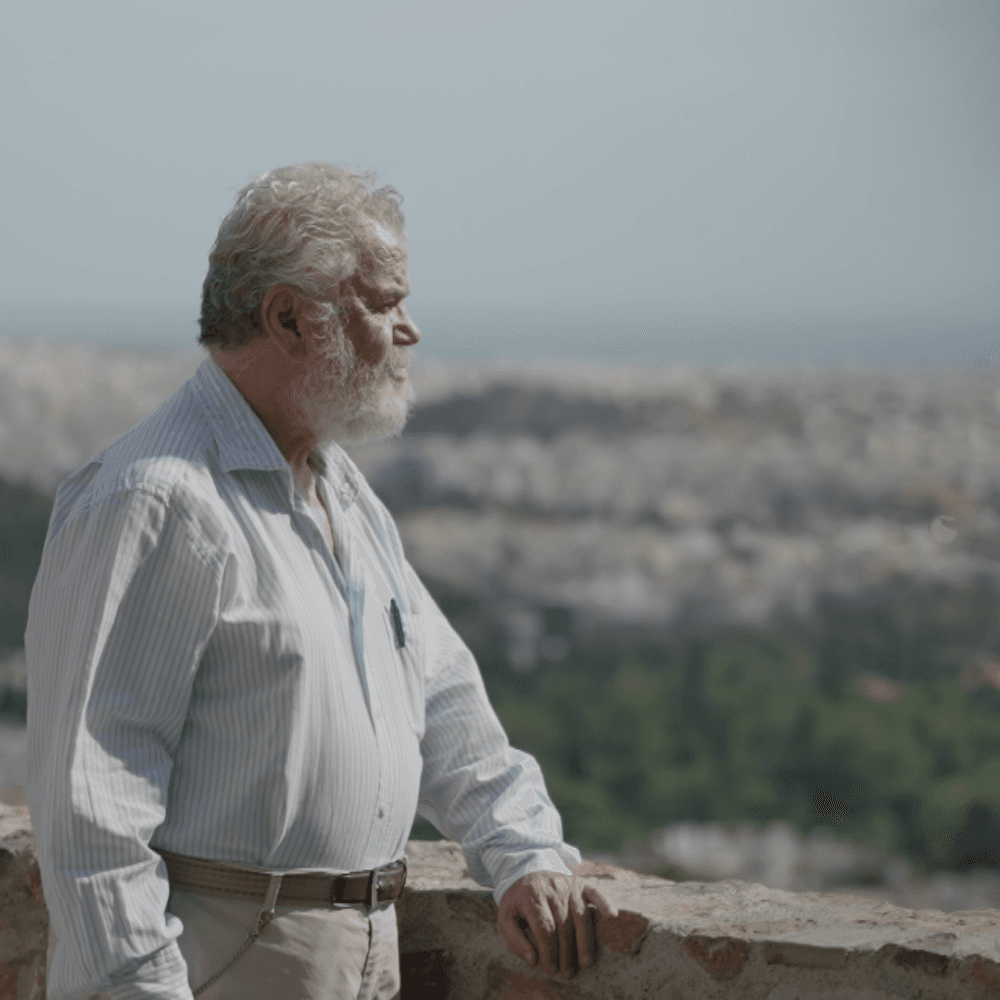

I was born up here, in the neighbourhood that we called, we still call, Tourkovounia. We were a large family, poor. My father was a worker. He’d got sick and had taken early retirement, from 1947, when I was born. I grew up in a beautiful neighbourhood. We were all poor families, all working class. So, our house was poor. Because we were poor, my father couldn't have his friends round for meze and wine, but they still come round and drank raki from Naxos and chatted. I’d listen in to them talking.

One of the first impressions that I formed was how hard their work was – those who had work – and how low their wages were and how poor they were. And I realised, at the age of twelve or fourteen, that my father's generation had had a hard life, which makes you see things differently. The difficulties of life. I don’t know what I really thought about the broader world and society in general. What played a role for me throughout my childhood was deciding what I wanted to be.

We hardly studied at all at primary school. We only played games. When I was in the third class, I said to my father, ‘I’ve had enough of the day school, I want to go to the evening school as well, like my brothers.’ And so, I went to the third class of high school in the evenings. And, just as I’d started, in the summer of 1961, Karamanlis made a law that increased the six years of evening school to seven. And the youth of the United Democratic Left – I still don’t know anything about the youth of the United Democratic Left – started a movement, saying that we ‘had to resist’. It started with strikes and meetings and ended with the various protests that we held. It was during this whole time at evening school that I became politically aware, with a kind of ‘I decide and do’ attitude.

I decided to become a doctor. I got into university to study medicine on the second attempt, in 1967, when the Junta come to power.

For me, the Junta didn't come as a surprise. I have a story about that. I had a girl; I was in a relationship with a girl. I was 20. We hadn’t started university yet, because we would start in the September and the coup happened in the April. Every Friday, I would meet her after her tutoring school in Kaningos Square, and take her to Ano Kypseli, where would talk about this and that – we were still young. One day, we were in Pedio tou Areos, and I said, ‘Sit down here, on the bench.’ And I said, ‘Look, there are difficult times coming. There’s going to be a dictatorship. There’ll be a junta, I’m sure of it. And I need to know if you’re prepared to stand by me.’ I did this because I knew her family was right wing. ‘Because I’m going to be involved. I’m going to get dragged in.’ And by ‘dragged in’, I meant jail or exile; things were going to get difficult. ‘Don't answer me now’, I said. ‘Think about it and let me know next Friday.’ She was younger than me, three years younger, 16 or 17 years old. And she found it really hard. The next Friday, she said ‘No’. So, I said, ‘That's OK. We’re good. I love you, you love me, but this is as far as we can go.’ But, of course, life can be strange.

Years passed. And at some point, she brought her mother to see me, as an ophthalmologist. We’re talking somewhere in the 2000s. I’ve never seen anyone cry that much. Nothing was said. Not ‘you were right’ or ‘you were wrong’, nothing. Such tears. She cried in my arms for five minutes. Nothing. We never got in touch again. Nothing. And you’re thinking, how does that work? I’ll take my hat off to anyone who knows the secret. That’s life.

At some point, a friend of mine, a fellow student at the evening school said to me, ‘Are we going to join such and such political organization?’ And he named the organization. And when he told me the name of the leader, a very well-known name in resistance circles, I said, ‘I don’t want to, Kostas.’ His name was Kostas. ‘I’m a poor kid, and I've got in to medicine. I’m going to finish my studies, become a doctor, and have quiet life.’ Anyway, I didn’t go. I went straight into the ‘20th October’ resistance organization. Giorgos Sagias, who I'd hung round with when we were both at school, before the Junta, said to me sometime, ‘I have a suggestion and it concerns you. We should join an organization that’s been started by some comrades and friends in Paris. They've set up the 20th October organization’. It took its name from the first bomb they had planted on 20th October 1969.

Time went on and it seemed like the Junta wasn’t going to fall or just get up and leave. They were arresting people, torturing them, and I was aware that others were being arrested and tortured and taken to jail, and what were we doing? Sitting on our hands, just looking on and waiting. So, we set up a cell and planted some bombs.

We made them ourselves with material that came from abroad and put them together with a power source and a timer. They were connected to detonators and a small battery. When they’d been planted, the battery sent out a charge, a circuit would be completed, the current went to the detonator, the detonator was set off and the explosive exploded.

The bombs were always planted taking into account how useful they would be, the conditions they would be planted in, and what dangers could the explosion create. This is why the bombs we planted were practically no real danger to anyone. But they went off at 2.30 in the morning. At 2.30 in the morning in those days, I don't know what it’s like now, but in those days nobody was at the street at those hours... Before planting the bomb, we would go by at 11.00, 11.30, at 2.00, at 3.00, we would go by with a girl. We would go by at times in order to see that there was no one around.

Our criteria for planting a bomb were that it should be a target that would cause them trouble and be symbolically acceptable at the same time. I’m talking about the propaganda headquarters’, the statue of Truman. Truman was the symbol of dependence on America, the dependence of Greece on America. Planting a bomb at the statue of Truman created a great deal of commotion.

The last bomb was at the power station in Katechaki. There is still a large Public Power Company substation there. According to the information we had at the time, this substation regulated the power supply in an area from Psychiko upwards towards the centre, up to the Panathenaic Stadium. The Hilton Hotel is inside this zone.

It was 20th October 1970, and Agnew, the vice president of America was staying at the Hilton. And we said, ‘We’re going to blow up the substation, and cut off the power to the Hilton and Papadopoulos’ house’. You get that this was an inspired target. But of course, we made a mistake. You always make one mistake. The bomb was placed under the large transformer. This created a huge magnetic field, and we hadn’t checked if the timer was anti-magnetic. And it wasn’t. So, as soon as it was planted that magnet stopped it and there was no explosion.

We were leaving by the stream, Sagias and I. We had cut some wire in the fence put up by the power company, and, as we were coming out of the stream we saw this guy, a working-class type, a little strange looking. It was 2.30 at night, 2.20, I don't remember exactly, what was he doing out on his own?

So, we had a dilemma. I talked about it briefly with Giorgos, and said, ‘We should get him, take him a little further over there, and scare the life out of him, so that he doesn’t talk.’ But Giorgos said no, and I didn’t really argue... We should have got him, but even tough revolutionaries make mistakes. We all get caught off guard sometimes. It’s one thing to grab someone and show him your weapon, to press its coldness against his cheek and say, ‘If you talk... Give me your ID card!’ to take it and know who he is, and another to just leave it. He made a phone call, and they came and caught us.

It's impossible to describe what it is about specific decisions you made 50 years ago. I’m now 77. When I decided in 1971 to carry weapons in my bag, my doctor’s bag, and go to plant bombs and risk taking the snitch who informed on us with us... I was 24. It wasn't a case of ‘my blood boiling.’ It was an attitude. Either you do something, or you don't. Either you just go through the motions, pretending, or, once you have made the decision to take part in armed resistance: armed resistance means armed resistance.

The held us in a room with two or three others. At some point, they took me and Sagias, put us in a car and took us to Skaramangas – I didn't know where they were taking us – and from there to a naval ship – we had no idea what it was – they locked us up in the hold and took us to Gyaros.

No one knew where we were going. The older ones – because there were several old people in there, very old, I mean over 70 –the older ones said, ‘They're most likely taking us there. Down to Gyaros.’ Because there were buildings there that had been built by prisoners in the past. And, indeed, that was where they were taking us.

That’s when things got difficult. There were twenty-nine metal beds that had to be carried – really heavy beds – from the beach in the bay where they’d been left by some ship. The mattresses, blankets, and luggage of all the old people had to be taken up. There were six, seven, or eight of us, I don’t remember. We were young. Young guys. Most of the young men, not all – because there were one or two of us who were so screwed up by torture that they couldn’t do anything – were able to take everything up, luggage, whatever, we carried it all up.

I liked it there. I liked it because it was an island, and I'd never been on holiday. I was 28, I’d never been on holiday, and this was an opportunity to learn to swim, because I didn’t know how. Towards the end of spring, it must have been May, I made various proposals to my comrades there. Many of them thought that...What do you call it these days? Thought I was 'trolling’ them, that I was having them on, but I wasn’t. I said, ‘Let's get together and tell them not to take us out of here before the end of September. We can stay here and rest and get our heads together. Either way, the Junta’s going to fall and they’ll disappear.’

We had water to wash with, but it was hard and full of sand. We made food ourselves, it was limited, but well-cooked and clean. We cooked it ourselves. There was one prisoner who had two or three helpers who helped with the distribution; taking the pot around the three dormitories.

There was once a storm, and they didn't bring food supplies. All we were orzo and lentils, orzo and lentils, so, at some point I said, ‘Guys, we have to do something....’ I complained to our people, the prisoners. They replied, ‘But what can we do?’ ‘Let's get someone to go down and get permission to catch to sheep.’ There were wild sheep roaming higher up. So, Nikos Karagiannis and I went up the hill and caught two huge sheep, 20 kilos each, and brought them back down. We slaughtered them and the guards had one and we had the other.

In Gyaros, there was no direct communication, there were only letters. Now, my mother was an old woman and illiterate, she couldn’t write, however, my sister could. I’d sent her a letter, asking her to find a specific sweet made of Chios mastic and send it to us. These were boxes weighing a kilo and the sweets inside they had concentrated ouzo, Chian mastic ouzo. In prison, we knew that if you mixed this liquid with 3 litres of water, I think, you got normal ouzo. Whenever they sent it to me, we made ouzo and 5 of us got together. Eventually, there would be 8 or 9 of us. We would sing and drink ouzo from coffee mugs so that it wasn’t obvious. The chief of security – he was from Kalamata – came. He came inside and smelled the ouzo, but he was too frightened to say anything, because there would be trouble. And there was no way he could handle it. Do you think they didn’t know their time was running out? They knew it.

We left over 23rd and 24th July. We didn't have a radio. The chief of security came and told us that we were free to go, but we couldn't right then for technical reasons. But a ship would come for us the next day.

Gyaros is a landmark of popular struggle. Of the Left, sure, but not just the Left. It's a place that should be preserved no matter what. It was built by prisoners of the very first generation of political prisoners. It was built under the whip and the cat-o-nine tails, by the socialists of the time. It shouldn’t be allowed to disappear.

There is no other way. The people either get involved in the struggle – not just for survival, but for progress – or they are lost. There is no other way. There is no life without struggle. Struggle is an innate part of human nature. The struggle for a better life. When I say– ‘a better life’, I don’t mean a richer life. Not at all. A better life is a just life, a peaceful life, when more good happens than bad. That’s what a just life is.