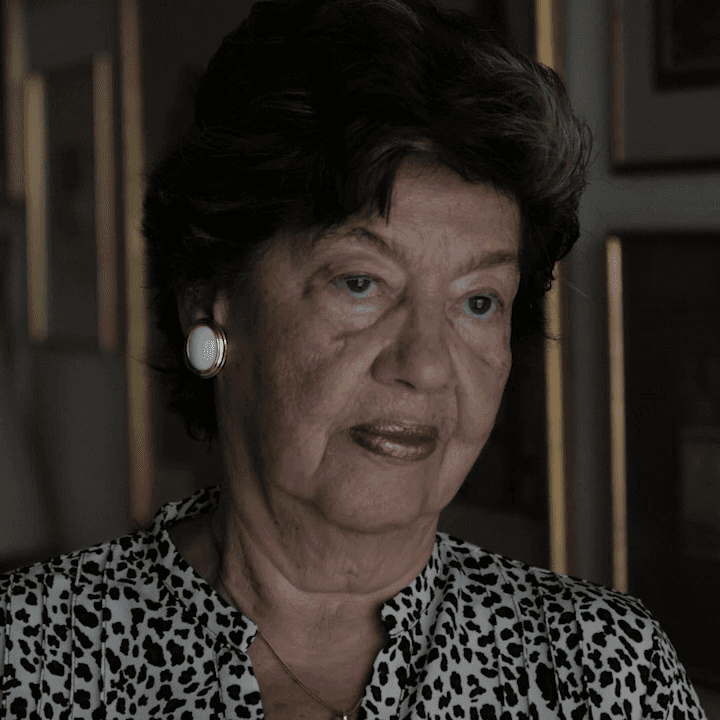

Irini Papatsaroucha: That's how my life started and it ends with Renio Missiou, the surname of my husband, Chronis Missios.

In '67, the dictatorship came about. Both of us were members of the Lambrakis Youth. Chronis was on the central council, an organizational secretary, and I was working on the magazine we published, called "Our Generation." That Spring, we were preparing for the Peace March and elections.

The dictatorship broke. We were at home. We lived at 126 Ippokratous Street. And we had little Katerina with us, who was just four years old. We had her with us because my sister was pregnant and had a difficult pregnancy.

So, on the evening of Friday, April 21, the door intercom buzzes. It's Takis Benas and he says, "Dictatorship. Run, Chronis!" Takis tells us that they have already arrested Rallis, Papandreou, and Kanellopoulos... And Takis goes into hiding too. Takis was the secretary of the Youth.

Chronis gathers whatever we had in our wallets and leaves. All we had was 200 drachma, really. So Chronis starts his life underground practically skint. As for me, I thought: "They’ve arrested political leaders. They’re not interested in people at my level. They’re interested in the top ones." And I’m trying to find a copy of the Constitution because I’m hearing on the radio which articles of the Constitution have been abolished, to see which articles have been done away with. Naturally, I was quite upset. Because it’s one thing to say, "It will happen, it will happen, it will happen," and another to hear, "It’s happened. The tanks have come out." And not knowing: will the person who left be able to hide? Will those in Thessaloniki be able to hide? My brother, a builder's union leader. Will he manage to hide? Where will he go? I froze. Terrified. But I thought: "Now is your time. This is your judgement." Because until then, I stood modestly before the great leaders and those who had been tortured. I thought, "Okay. This person knows, he or she has been tested. You haven’t been tested."

George Votsis, the journalist, passed by to see me. On his way out, the apartment door was next to the elevator door and at that moment, we both had the same thought: that it might be the last time we see each other. We hugged and kissed. George left. I went back in. Shortly after, the doorbell rang again. It was Themis Banousis. He brought me his wife, Maria. A beautiful young woman from Crete. They had eloped and married because her family didn’t approve of him. Themis left as well. And Maria and I were left together.

Shortly after, the doorbell rings again, and the Security Police arrived. Katerina was sleeping on a cot that we had set up in our room. My mother was also with us. My mother, with a heavy heart, had lived through all this before. She had experienced it before and hoped that at least I would be spared. Everyone hoped so. That the difficult times had passed, and that we now lived in a democracy.

They enter, furious, I don’t even remember how many men there were. And they search the house. “Where is your husband?” I, the epitome of a law-abiding citizen: “My husband is in Patras for the election campaign.” We were preparing for elections, remember? I wanted to rub it in their faces that they were the ones operating outside the Law, whereas we were well within our rights. Yes, yes, yes, I know, how naïve was I… He says: “But his shoes are here.” “Well, he doesn’t only have one pair of shoes,” I say.

In the meantime, while they were searching, little Katerina woke up. You know, kids wake up with rosy cheeks. I saw the color drain from her cheeks. Because she understood what was happening, she knew. So, while pretending to tidy up things, I emptied the contents of my bag onto the bed, mixing it with the covers that they had already messed up, and I only took a few things. Because I was afraid I might have something in my bag that I shouldn’t. I put on my nice suit, and left with the offiers.

At the 5th precinct, they took my information, and I saw my file; it was nice and large. They sent me down to the holding cell. And there, I found Avra Partsalidou, the Kiàou couple, Vangelio Logara, the father of Aleka Papariga... and I thought: “If they count me among these leading figures, I’m in big trouble!” Whenever I am extremely anxious, I feel as if my brain isn’t getting enough blood, I get dizzy and sleepy. I had leant my head on the shoulder of Aleka’s father and was dozing. But I was listening. “She’s young, and doesn’t know what’s coming, poor thing. That’s why she’s sleeping.” And I thought to myself: “It’s precisely because I do know what’s coming that I’m trying to escape, by sleeping.”

From there, they took us in the afternoon and transferred us to the racetrack grounds. They were gathering people from different precincts at the racetrack.

As we passed through Syntagma square, all the streets were deserted, deserted, people were terrified, and kept indoors. In front of the Monument of the Unknown Soldier, a female tourist, had laid down, mimicking the pose of the Unknown Soldier. I was very disturbed by this image and thought: “Look at that.”

They take us to the racetrack. There, it crosses my mind: “They might execute us.” Because as we were getting off, I saw soldiers with bayonets fixed, in two rows, one on either side of us. And I thought: “They are going to execute us. They are leading us to execution.”

We had nothing. No blankets, no clothes, nothing, nothing, nothing. I went with my little handbag, a very nice handbag I’ll have you know, yes, and a cinnamon-colored suit and a lace blouse that my mother had knitted for me. Why? In such situations, I want to present in a way that defies reality. That’s why I went dressed as if for a happy occasion. And I remained in that happy occasion attire for one and a half, two months in exile, until the packages from home arrived. With the suit and the dainty little pumps and the nylon stockings which had become threadbare. What runs! There were more holes and runs than there was stocking!

Anyhow, at the racetrack, they put the women in one area and the men in another. Anna Solomou had her little child, Maki, with her. I kind od took charge of him while we were there, telling him stories and fairy tales and this and that. And we were singing, singing Theodorakis songs inside the racetrack. However, we later realized that a terrible thing had happened next door, where the men were held. They had beaten Iliou very badly and killed Panagiotis Elis. He was the first victim of the dictatorship, Panagiotis Elis. For no reason. For nothing. And after Elis’s assassination, the black beret who Killed him came in. If I were to say “like a rabid dog,” I’d have to apologize to the dogs. He walked among us as if he couldn’t see us; if you happened to be in his path, he would step on you. We were frozen along the wall. He took a couple of furious rounds inside and then left. So we understood that something horrific had happened. And shortly after, we learned that they had killed Panagiotis.

From the racetrack, they transferred us to Skaramangas. We boarded military ships and set off for some island. But we didn’t know which island.

Inside the ship's hold, we met with people who had been imprisoned and exiled before. Also new people, who had never been before. Upset, anxious. We were all anxious. We didn’t know what awaited us. We didn’t know where we were going. There were various guesses. But most said: “Gyaros.”

Indeed, we were taken to Gyaros. And it was a sweet sight. A very sweet sight. It was a lovely April afternoon. Gyaros was green, with that small grass that sprouts even on the rocks in Spring. I don’t know how the others reacted, but a sense of peace came over me. And when the hatches opened, we saw the terraced levels that the previous exiles had shaped in order to pitch their tents. And in the middle, between the two bays, was the building. Built of brick.

We took the path uphill. Our first thought was: “Will they beat us now, as we go down one by one?” No beatings occurred. And guard was barely visible. We learned that the first guard of Gyaros was itself in an exile of sorts. They were former members of the Parliament’s guard, who were rounded up and sent to the island because they were considered “corrupt,” having been in contact the Parliament and MPs. For them, “corruption” was democracy.

We landed on an uninhabited island. A prison that had been closed since ‘61. The door was ajar, wide open and a long corridor, pitch-dark, filthy, reeking of rodent and possibly human urine. Such filth! We were the first to enter. We were the first. Men and women. Of course, men and women were placed in separate wings. There were toilets, which, however, were not usable, they were filthy, and there was no water. None, not a drop. They had to bring it with a water tanker. The conditions were miserable. The windows were broken, there were windows through which the rain came in, and it raised the issue of who would sleep beneath the window. Eventually, I said: “Fine, I will.” We didn’t have cots. Very few, extremely few, had cots. Our male fellow prisoners fabricated makeshift burlap mattresses stuffed with straw for us. I slept on the floor until my mother managed to send me a cot after two months, which served me throughout my captivity.

At first, we didn’t have meals. We ate dry food. At Easter, for example, we were fed canned food. They had transferred us on Holy Wednesday. On Easter Day of ‘67 in Gyaros, amidst the general gloom, two people appeared, a man and a woman, singing and dancing: “Here atop the tender grass, what a tremendous dance will take place.” And who do you think they were? Stefanos and Renio, Stefanos and I.

In the dormitory, I was lucky because the in second berth next to mine was Vasso Katraki. Next to Vasso was Eleni Kamoulakou, and after me was Dora Psaltopoulou, an old EPON member who had been imprisoned with my sisters and now got the chance to meet the youngest Papatsaroucha. There was no privacy. Most people didn’t have clothes with them. I had a shirt that my mother gave me. Well, that shirt was worn by whoever could fit into it, while they washed their own, so it was everyone’s stand-in top.

The dictator Pattakos had come to Gyaros. He came to our dormitory. And there, Eleni Falianga, a teacher, confronted him about our rights and so on, and Pattakos couldn’t get a word in edgewise. And as he left, he made this hand gesture, as if to say: “They should cut their tongues out with scissors.” And he left, certain that we needed to be exterminated.

More and more people kept arriving. At some point, there must have been around 6,000 of us. We couldn’t all fit. They set up tents. They set up tents in both bays, on the fourth and fifth cove too, on the left and the right of the prison. There was also an attempt at a semblance of organization, of networking. I participated in the mechanism for spreading news. When we were taken out for a walk, someone might have had a contact, and so, from person to person, the news bulletin passed. They told me that I should head the youth faction, representing the young women. And I said: “Elections. Because the girls might not want me; they might want someone else.” “Ah,” they said, “elections under such conditions aren’t possible.” “Well, then I won’t be responsible,” I said.

During that summer, three or four times, they called me down to the administration office, always the same young man, who introduced himself with a name that varied in ending but always started with Anastas-: Anastasiadiss, Anastasakos, Anastasakis, a different name each time. He pretended to be my friend, telling me things like: “So-and-so made a statement, so-and-so signed a disclaimer” and “Sign a statement so you can leave.” “I will do no such thing.” Once, twice, three times… the last time he calls me into his office, where his bed was, unmade. “Sit down,” he says. I said: “I don’t see a chair.” “It’s okay, sit on the bed.”

I was really frightened. Where would I sit? A 27-28-year-old Rinio. Where would I sit? “No,” I said, “it’s okay, we don’t have much to say anyway, we’ve said everything. What do you want from me?” “Make a statement.” “Why should I make a statement and what should I renounce?” “The Communist Party.” I said: “I told you, I won’t make a statement because I have nothing to renounce, I’m not a communist.” “Since you’re not a communist,” he said, “why don’t you renounce it?” “Because I wouldn’t renounce even Buddhism, any -ism. I wouldn’t renounce anything under dictation,” I said, “not even the daisy I wear on my lapel.” But that time, I was terrified because I saw the unmade bed and the “sit down,” yes, you get the picure… the administration office was down by the sea, quite a long distance from the prisons and the women’s dormitories. Even if you were to scream, who would hear you? Who would hear you? So, I said: “Tell me, if I admit that I’m a communist, will you stop calling me?” He said: “Yes.” “Well then, I am.” And indeed, they stopped calling me. But it was the only time I declared myself a communist. And that was the end of that.

There were no torture, but there were many other deprivations. For example, they could deprive you of correspondence. They deprived me of it for two months, and I didn’t know what was happening in the world. At some point, a letter came through announcing my father’s death in Poland and the death of my sister’s newborn. Two months without a letter, and when this one came, they gave it to me. With the two deaths. Because my father had left as a guerrilla. After the defeat, the guerrillas escaped to the various people's republics. He died alone in Zgorzelec, and a few comrades found him when he didn’t show up for two or three days; they went and found him dead, at home.

I collapsed. I broke down. I had a nervous breakdown. I stayed in bed for three days, unable to get up, dizzy, unable to eat anything, and vomiting uncontrollably. And then I learned to make a makeshift saline solution: In a bottle of water, lemon, sugar, and salt, just enough so that no taste overpowers the others. Because I was at risk of dehydration. These were the kinds of torture in Gyaros.

The other thing is the concern you have when leaving your family behind. My mother lost ten kilos in fifteen days. There were families deprived of their sole financial support, whether it was the father or the son. There were children left without their parents, like the young son of Ourania Nizamidou. Both Ourania and her husband were in Gyaros. Their older son, Yiannis, was a soldier, and the little child was left alone in Giannitsa. The neighbors gave him food, but none dared to take him into their home. The child slept under the stairs. You think, "Okay, I am defending my ideas and my dignity, but do I have the right to place such a burden on my children, my mother, my wife? Do I have the right? Don’t they have their own dignity to defend?" Just so that you can be the hero, at peace with yourself. And when you have a conscience, this is very tough. Extremely tough. Especially for the mothers who had left children behind. I saw mothers crying at night, filled with anxiety and guilt, but secretly, so it wouldn’t show. I remember Ourania Nizamidou walking around until late. I was outside too. I stayed to listen to the news; Ourania couldn’t sleep because she was thinking about her child, outside.

I never gave up reading. Never. Never. In Gyaros, I slept with Elytis under my pillow. Once, when a fellow inmate asked me, "What is this book you read every day? Lend it to me." I watched her, and as soon as she fell asleep, I quietly took it from under her pillow so I wouldn’t be deprived. Reading, you see, is a great relief. And reading always comforted me.

In the afternoon, I took off my little suit, shook it well after the shift was over, the carrying, the wheelbarrow, the rubble, all of that, and I brushed my hair, shook out my clothes, put on my threadbare stockings and stuck a daisy on my lapel, and went for a walk. We were allowed to go for a walk. I dressed up, defending beauty both inwardly and outwardly. Because beauty is a duty. And beauty is a blessing. "Beauty will save the world." That’s what I have always believed.

On August 28, 1968, we were transferred from Gyaros to Crete, to Heraklion, to the suburb of Alikarnassos. There are prisons there. The men left in two groups and were taken to Leros, to Partheni and Lakki, and then us women were sent to Alikarnassos. We were preventively detained but lived in prison conditions. Preventively detained for so many years is inconceivable under democratic legislation. For the Junta, everything was taken for granted, including cold-blooded murders. Indeed, conditions were better in an inhabited area; we were not isolated, we could shout if something happened, and people would hear us.

Only this once… Very close to the Alikarnassos prison, there was a football field, and there was a match being played. We thought, "Now's our chance." We gathered at the window, large windows, glass panes in the stairwell, all of us there so that people would see us and understand that there were prisoners here. The men of Crete saw us and started making gestures. Yes. And here we were, thinking that "the democratic people of Crete would be moved by our presence.” What a lark! The democratic people made other kinds of gestures, not gestures of support, if you get my drift.

Many men left after signing declarations, a great many. For women, signing a declaration was very rare. At the end of August 1970, Chronis had a dream: There was a shipwreck, I was on the ship, and only twenty-one women were saved. Chronis thought, "I hope my Rina managed to survive because I taught her well how to swim," and he kept thinking hat to himself after he awoke. There was a rumour circulating that an amnesty would be granted. The list of women arrived, and they started reading it out. They said, "Twenty-one women are being released." And they read. And read. And read. And read. And my blood froze. Because it went eighteen, nineteen, twenty… The last three were three classicists: Eleni Garidi, Irini Tsakiri, and Irini Papatsaroucha. Twenty-first! “And Irini Papatsaroucha”. Chronis' dream, right? That he had taught his girl to swim well and hoped she survived. I was the twenty-first. But up until the twenty-first name was heard, I nearly went mad.

This term of nearly three and a half years, helped me build the courage to defend my views, whatever the cost. Let me tell you, my dear; in hardships, in deprivations, you discover abilities, strengths, and traits that life doesn’t otherwise give you the opportunity to discover. Some people wither away. Some people are merely loyal to the political line. Fortunately, for me, my participation was a matter of conscience since my younges age. A matter of personal importance. And that’s what kept me going; This conscience. This conscience is the little vessel, the walnut shell, that helps you stay afloat and endure all the turmoil. And for me, it was a personal matter. Democracy is my personal matter. As it should be the personal matter of all citizens. I came out on top, just so.